Table of Contents

Introduction

Way back in the late 1920s John Von Neumann established the main problem in game theory that has remained relevant still today:

Players s1, s2, …, sn are playing a given game G. Which moves should player sm play to achieve the best possible outcome?

Shortly after, problems of this kind grew into a challenge of great significance for development of one of today’s most popular fields in computer science – artificial intelligence. Some of the greatest accomplishments in artificial intelligence are achieved on the subject of strategic games – world champions in various strategic games have already been beaten by computers, e.g. in Chess, Checkers, Backgammon, and most recently (2016) even Go.

Although these programs are very successful, their way of making decisions is a lot different than that of humans. The majority of these programs are based on efficient searching algorithms, and since recently on machine learning as well.

The Minimax algorithm is a relatively simple algorithm used for optimal decision-making in game theory and artificial intelligence. Again, since these algorithms heavily rely on being efficient, the vanilla algorithm’s performance can be heavily improved by using alpha-beta pruning – we’ll cover both in this article.

Although we won’t analyze each game individually, we’ll briefly explain some general concepts that are relevant for two-player non-cooperative zero-sum symmetrical games with perfect information – Chess, Go, Tic-Tac-Toe, Backgammon, Reversi, Checkers, Mancala, 4 in a row etc…

As you probably noticed, none of these games are ones where e.g. a player doesn’t know which cards the opponent has, or where a player needs to guess about certain information.

Defining Terms

Rules of many of these games are defined by legal positions (or legal states) and legal moves for every legal position. For every legal position it is possible to effectively determine all the legal moves. Some of the legal positions are starting positions and some are ending positions.

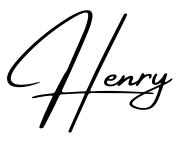

The best way to describe these terms is using a tree graph whose nodes are legal positions and whose edges are legal moves. The graph is directed since it does not necessarily mean that we’ll be able to move back exactly where we came from in the previous move, e.g. in chess a pawn can only go forward. This graph is called a game tree. Moving down the game tree represents one of the players making a move, and the game state changing from one legal position to another.

Here’s an illustration of a game tree for a tic-tac-toe game:

Grids colored blue are player X’s turns, and grids colored red are player O’s turns. The ending position (leaf of the tree) is any grid where one of the players won or the board is full and there’s no winner.

The complete game tree is a game tree whose root is starting position, and all the leaves are ending positions. Each complete game tree has as many nodes as the game has possible outcomes for every legal move made. It is easy to notice that even for small games like tic-tac-toe the complete game tree is huge. For that reason it is not a good practice to explicitly create a whole game tree as a structure while writing a program that is supposed to predict the best move at any moment. Yet, the nodes should be created implicitly in the process of visiting.

We’ll define state-space complexity of a game as a number of legal game positions reachable from the starting position of the game, and branching factor as the number of children at each node (if that number isn’t constant, it’s a common practice to use an average).

For tic-tac-toe, an upper bound for the size of the state space is 39=19683. Imagine that number for games like chess! Hence, searching through whole tree to find out what’s our best move whenever we take turn would be super inefficient and slow.

This is why Minimax is of such a great significance in game theory.

Theory Behind Minimax

The Minimax algorithm relies on systematic searching, or more accurately said – on brute force and a simple evaluation function. Let’s assume that every time during deciding the next move we search through a whole tree, all the way down to leaves. Effectively we would look into all the possible outcomes and every time we would be able to determine the best possible move.

However, for non-trivial games, that practice is inapplicable. Even searching to a certain depth sometimes takes an unacceptable amount of time. Therefore, Minimax applies search to a fairly low tree depth aided with appropriate heuristics, and a well designed, yet simple evaluation function.

With this approach we lose the certainty in finding the best possible move, but the majority of cases the decision that minimax makes is much better than any human’s.

Now, let’s take a closer look at the evaluation function we’ve previously mentioned. In order to determine a good (not necessarily the best) move for a certain player, we have to somehow evaluate nodes (positions) to be able to compare one to another by quality.

The evaluation function is a static number, that in accordance with the characteristics of the game itself, is being assigned to each node (position).

It is important to mention that the evaluation function must not rely on the search of previous nodes, nor of the following. It should simply analyze the game state and circumstances that both players are in.

It is necessary that the evaluation function contains as much relevant information as possible, but on the other hand – since it’s being calculated many times – it needs to be simple.

Usually it maps the set of all possible positions into symmetrical segment:

Value of M is being assigned only to leaves where the winner is the first player, and value -M to leaves where the winner is the second player.

In zero-sum games, the value of the evaluation function has an opposite meaning – what’s better for the first player is worse for the second, and vice versa. Hence, the value for symmetric positions (if players switch roles) should be different only by sign.

A common practice is to modify evaluations of leaves by subtracting the depth of that exact leaf, so that out of all moves that lead to victory the algorithm can pick the one that does it in the smallest number of steps (or picks the move that postpones loss if it is inevitable).

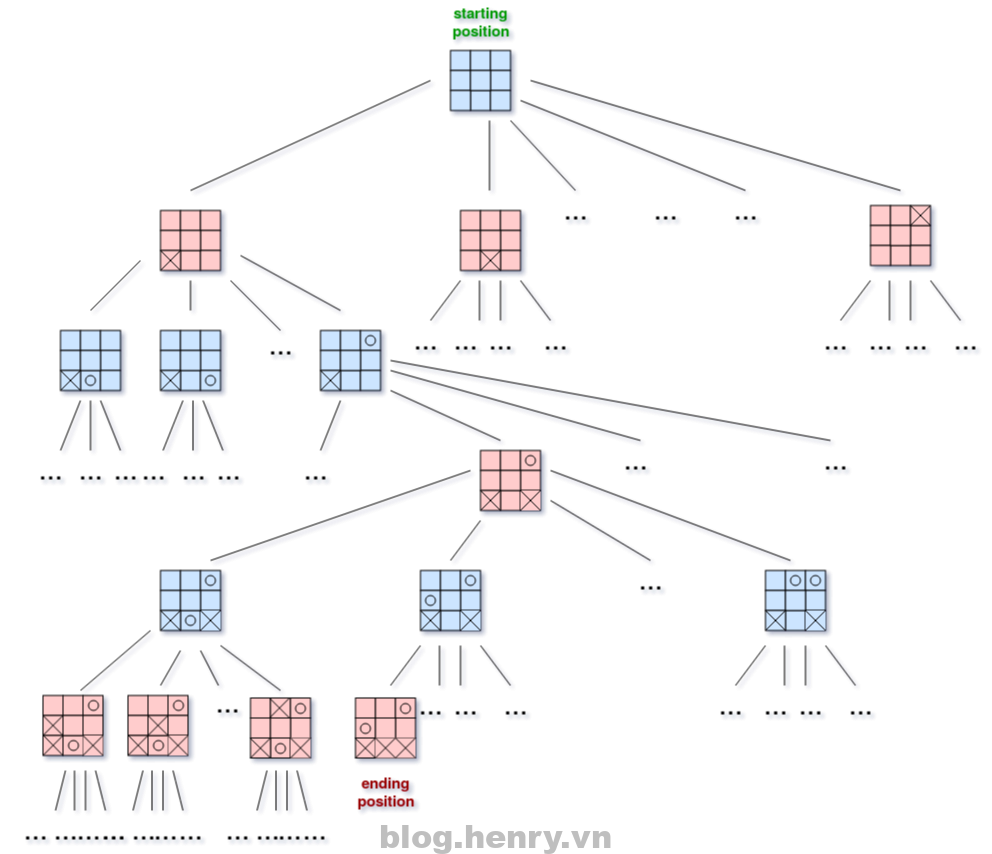

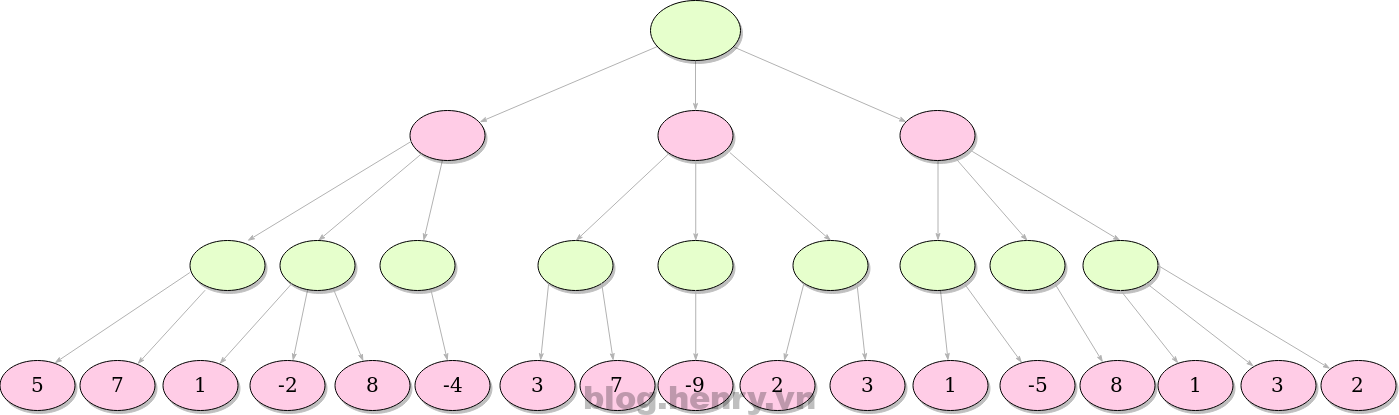

Here’s a simple illustration of Minimax’ steps. We’re looking for the minimum value, in this case.

The green layer calls the Max() method on nodes in the child nodes and the red layer calls the Min() method on child nodes.

- Evaluating leaves:

- Deciding the best move for green player using depth 3:

The idea is to find the best possible move for a given node, depth, and evaluation function.

In this example we’ve assumed that the green player seeks positive values, while the pink player seeks negative. The algorithm primarily evaluates only nodes at the given depth, and the rest of the procedure is recursive. The values of the rest of the nodes are the maximum values of their respective children if it’s green player’s turn, or, analogously, the minimum value if it’s pink player’s turn. The value in each node represents the next best move considering given information.

While searching the game tree, we’re examining only nodes on a fixed (given) depth, not the ones before, nor after. This phenomenon is often called the horizon effect.

Opening Books and Tic-Tac-Toe

In strategic games, instead of letting the program start the searching process in the very beginning of the game, it is common to use the opening books – a list of known and productive moves that are frequent and known to be productive while we still don’t have much information about the state of game itself if we look at the board.

In the beginning, it is too early in the game, and the number of potential positions is too great to automatically decide which move will certainly lead to a better game state (or win).

However, the algorithm reevaluates the next potential moves every turn, always choosing what at that moment appears to be the fastest route to victory. Therefore, it won’t execute actions that take more than one move to complete, and is unable to perform certain well known “tricks” because of that. If the AI plays against a human, it is very likely that human will immediately be able to prevent this.

If, on the other hand, we take a look at chess, we’ll quickly realize the impracticality of solving chess by brute forcing through a whole game tree. To demonstrate this, Claude Shannon calculated the lower bound of the game-tree complexity of chess, resulting in about 10120 possible games.

Just how big is that number? For reference, if we compared the mass of an electron (10-30kg) to the mass of the entire known universe (1050-1060kg), the ratio would be in order of 1080-1090.

That’s ~0.0000000000000000000000000000000001% of the Shannon number.

Imagine tasking an algorithm to go through every single of those combinations just to make a single decision. It’s practically impossible to do.

Even after 10 moves, the number of possible games is tremendously huge:

| Number of moves | Number of possible games |

|---|---|

| 1 | 20 |

| 2 | 40 |

| 3 | 8,902 |

| 4 | 197,281 |

| 5 | 4,865,609 |

| 6 | 119,060,324 |

| 7 | 3,195,901,860 |

| 8 | 84,998,978,956 |

| 9 | 2,439,530,234,167 |

| 10 | 69,352,859,712,417 |

Let’s take this example to a tic-tac-toe game. As you probably already know, the most famous strategy of player X is to start in any of the corners, which gives the player O the most opportunities to make a mistake. If player O plays anything besides center and X continues his initial strategy, it’s a guaranteed win for X. Opening books are exactly this – some nice ways to trick an opponent in the very beginning to get advantage, or in best case, a win.

To simplify the code and get to the core of algorithm, in the example in the next chapter we won’t bother using opening books or any mind tricks. We’ll let the minimax search from the start, so don’t be surprised that algorithm never recommends the corner strategy.

Minimax Implementation in Python

In the code below, we will be using an evaluation function that is fairly simple and common for all games in which it’s possible to search the whole tree, all the way down to leaves.

It has 3 possible values:

- -1 if player that seeks minimum wins

- 0 if it’s a tie

- 1 if player that seeks maximum wins

Since we’ll be implementing this through a tic-tac-toe game, let’s go through the building blocks. First, let’s make a constructor and draw out the board:

# We'll use the time module to measure the time of evaluating

# game tree in every move. It's a nice way to show the

# distinction between the basic Minimax and Minimax with

# alpha-beta pruning :)

import time

class Game:

def __init__(self):

self.initialize_game()

def initialize_game(self):

self.current_state = [['.','.','.'],

['.','.','.'],

['.','.','.']]

# Player X always plays first

self.player_turn = 'X'

def draw_board(self):

for i in range(0, 3):

for j in range(0, 3):

print('{}|'.format(self.current_state[i][j]), end=" ")

print()

print()

All of the proceeding methods, except for the main method, belong to the Game class.

We’ve talked about legal moves in the beginning sections of the article. To make sure we abide by the rules, we need a way to check if a move is legal:

# Determines if the made move is a legal move

def is_valid(self, px, py):

if px < 0 or px > 2 or py < 0 or py > 2:

return False

elif self.current_state[px] != '.':

return False

else:

return True

Then, we need a simple way to check if the game has ended. In tic-tac-toe, a player can win by connecting three consecutive symbols in either a horizontal, diagonal or vertical line:

# Checks if the game has ended and returns the winner in each case

def is_end(self):

# Vertical win

for i in range(0, 3):

if (self.current_state[0][i] != '.' and

self.current_state[0][i] == self.current_state[1][i] and

self.current_state[1][i] == self.current_state[2][i]):

return self.current_state[0][i]

# Horizontal win

for i in range(0, 3):

if (self.current_state[i] == ['X', 'X', 'X']):

return 'X'

elif (self.current_state[i] == ['O', 'O', 'O']):

return 'O'

# Main diagonal win

if (self.current_state[0][0] != '.' and

self.current_state[0][0] == self.current_state[1][1] and

self.current_state[0][0] == self.current_state[2][2]):

return self.current_state[0][0]

# Second diagonal win

if (self.current_state[0][2] != '.' and

self.current_state[0][2] == self.current_state[1][1] and

self.current_state[0][2] == self.current_state[2][0]):

return self.current_state[0][2]

# Is whole board full?

for i in range(0, 3):

for j in range(0, 3):

# There's an empty field, we continue the game

if (self.current_state[i][j] == '.'):

return None

# It's a tie!

return '.'

The AI we play against is seeking two things – to maximize its own score and to minimize ours. To do that, we’ll have a max() method that the AI uses for making optimal decisions.

# Player 'O' is max, in this case AI

def max(self):

# Possible values for maxv are:

# -1 - loss

# 0 - a tie

# 1 - win

# We're initially setting it to -2 as worse than the worst case:

maxv = -2

px = None

py = None

result = self.is_end()

# If the game came to an end, the function needs to return

# the evaluation function of the end. That can be:

# -1 - loss

# 0 - a tie

# 1 - win

if result == 'X':

return (-1, 0, 0)

elif result == 'O':

return (1, 0, 0)

elif result == '.':

return (0, 0, 0)

for i in range(0, 3):

for j in range(0, 3):

if self.current_state[i][j] == '.':

# On the empty field player 'O' makes a move and calls Min

# That's one branch of the game tree.

self.current_state[i][j] = 'O'

(m, min_i, min_j) = self.min()

# Fixing the maxv value if needed

if m > maxv:

maxv = m

px = i

py = j

# Setting back the field to empty

self.current_state[i][j] = '.'

return (maxv, px, py)

However, we will also include a min() method that will serve as a helper for us to minimize the AI’s score:

# Player 'X' is min, in this case human

def min(self):

# Possible values for minv are:

# -1 - win

# 0 - a tie

# 1 - loss

# We're initially setting it to 2 as worse than the worst case:

minv = 2

qx = None

qy = None

result = self.is_end()

if result == 'X':

return (-1, 0, 0)

elif result == 'O':

return (1, 0, 0)

elif result == '.':

return (0, 0, 0)

for i in range(0, 3):

for j in range(0, 3):

if self.current_state[i][j] == '.':

self.current_state[i][j] = 'X'

(m, max_i, max_j) = self.max()

if m < minv:

minv = m

qx = i

qy = j

self.current_state[i][j] = '.'

return (minv, qx, qy)

And ultimately, let’s make a game loop that allows us to play against the AI:

def play(self):

while True:

self.draw_board()

self.result = self.is_end()

# Printing the appropriate message if the game has ended

if self.result != None:

if self.result == 'X':

print('The winner is X!')

elif self.result == 'O':

print('The winner is O!')

elif self.result == '.':

print("It's a tie!")

self.initialize_game()

return

# If it's player's turn

if self.player_turn == 'X':

while True:

start = time.time()

(m, qx, qy) = self.min()

end = time.time()

print('Evaluation time: {}s'.format(round(end - start, 7)))

print('Recommended move: X = {}, Y = {}'.format(qx, qy))

px = int(input('Insert the X coordinate: '))

py = int(input('Insert the Y coordinate: '))

(qx, qy) = (px, py)

if self.is_valid(px, py):

self.current_state[px] = 'X'

self.player_turn = 'O'

break

else:

print('The move is not valid! Try again.')

# If it's AI's turn

else:

(m, px, py) = self.max()

self.current_state[px] = 'O'

self.player_turn = 'X'

Let’s start the game!

def main():

g = Game()

g.play()

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

Now we’ll take a look at what happens when we follow the recommended sequence of turns – i.e. we play optimally:

.| .| .|

.| .| .|

.| .| .|

Evaluation time: 5.0726919s

Recommended move: X = 0, Y = 0

Insert the X coordinate: 0

Insert the Y coordinate: 0

X| .| .|

.| .| .|

.| .| .|

X| .| .|

.| O| .|

.| .| .|

Evaluation time: 0.06496s

Recommended move: X = 0, Y = 1

Insert the X coordinate: 0

Insert the Y coordinate: 1

X| X| .|

.| O| .|

.| .| .|

X| X| O|

.| O| .|

.| .| .|

Evaluation time: 0.0020001s

Recommended move: X = 2, Y = 0

Insert the X coordinate: 2

Insert the Y coordinate: 0

X| X| O|

.| O| .|

X| .| .|

X| X| O|

O| O| .|

X| .| .|

Evaluation time: 0.0s

Recommended move: X = 1, Y = 2

Insert the X coordinate: 1

Insert the Y coordinate: 2

X| X| O|

O| O| X|

X| .| .|

X| X| O|

O| O| X|

X| O| .|

Evaluation time: 0.0s

Recommended move: X = 2, Y = 2

Insert the X coordinate: 2

Insert the Y coordinate: 2

X| X| O|

O| O| X|

X| O| X|

It's a tie!

As you’ve noticed, winning against this kind of AI is impossible. If we assume that both player and AI are playing optimally, the game will always be a tie. Since the AI always plays optimally, if we slip up, we’ll lose.

Take a close look at the evaluation time, as we will compare it to the next, improved version of the algorithm in the next example.

Alpha-Beta Pruning

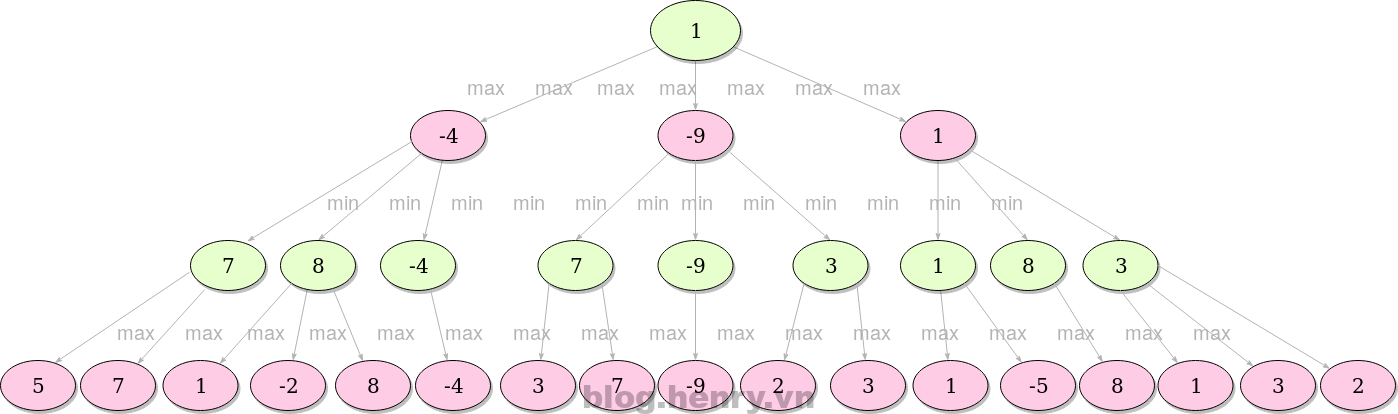

Alpha–beta (𝛼−𝛽) algorithm was discovered independently by a few researches in mid 1900s. Alpha–beta is actually an improved minimax using a heuristic. It stops evaluating a move when it makes sure that it’s worse than previously examined move. Such moves need not to be evaluated further.

When added to a simple minimax algorithm, it gives the same output, but cuts off certain branches that can’t possibly affect the final decision – dramatically improving the performance.

The main concept is to maintain two values through whole search:

- Alpha: Best already explored option for player Max

- Beta: Best already explored option for player Min

Initially, alpha is negative infinity and beta is positive infinity, i.e. in our code we’ll be using the worst possible scores for both players.

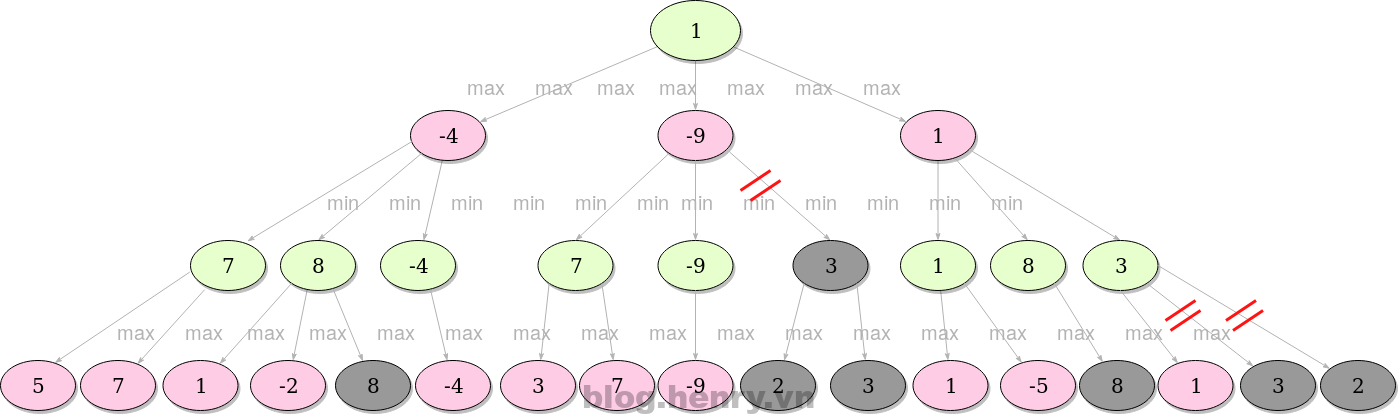

Let’s see how the previous tree will look if we apply alpha-beta method:

When the search comes to the first grey area (8), it’ll check the current best (with minimum value) already explored option along the path for the minimizer, which is at that moment 7. Since 8 is bigger than 7, we are allowed to cut off all the further children of the node we’re at (in this case there aren’t any), since if we play that move, the opponent will play a move with value 8, which is worse for us than any possible move the opponent could have made if we had made another move.

A better example may be when it comes to a next grey. Note the nodes with value -9. At that point, the best (with maximum value) explored option along the path for the maximizer is -4. Since -9 is less than -4, we are able to cut off all the other children of the node we’re at.

This method allows us to ignore many branches that lead to values that won’t be of any help for our decision, nor they would affect it in any way.

With that in mind, let’s modify the min() and max() methods from before:

def max_alpha_beta(self, alpha, beta):

maxv = -2

px = None

py = None

result = self.is_end()

if result == 'X':

return (-1, 0, 0)

elif result == 'O':

return (1, 0, 0)

elif result == '.':

return (0, 0, 0)

for i in range(0, 3):

for j in range(0, 3):

if self.current_state[i][j] == '.':

self.current_state[i][j] = 'O'

(m, min_i, in_j) = self.min_alpha_beta(alpha, beta)

if m > maxv:

maxv = m

px = i

py = j

self.current_state[i][j] = '.'

# Next two ifs in Max and Min are the only difference between regular algorithm and minimax

if maxv >= beta:

return (maxv, px, py)

if maxv > alpha:

alpha = maxv

return (maxv, px, py)

def min_alpha_beta(self, alpha, beta):

minv = 2

qx = None

qy = None

result = self.is_end()

if result == 'X':

return (-1, 0, 0)

elif result == 'O':

return (1, 0, 0)

elif result == '.':

return (0, 0, 0)

for i in range(0, 3):

for j in range(0, 3):

if self.current_state[i][j] == '.':

self.current_state[i][j] = 'X'

(m, max_i, max_j) = self.max_alpha_beta(alpha, beta)

if m < minv:

minv = m

qx = i

qy = j

self.current_state[i][j] = '.'

if minv <= alpha:

return (minv, qx, qy)

if minv < beta:

beta = minv

return (minv, qx, qy)

And now, the game loop:

def play_alpha_beta(self):

while True:

self.draw_board()

self.result = self.is_end()

if self.result != None:

if self.result == 'X':

print('The winner is X!')

elif self.result == 'O':

print('The winner is O!')

elif self.result == '.':

print("It's a tie!")

self.initialize_game()

return

if self.player_turn == 'X':

while True:

start = time.time()

(m, qx, qy) = self.min_alpha_beta(-2, 2)

end = time.time()

print('Evaluation time: {}s'.format(round(end - start, 7)))

print('Recommended move: X = {}, Y = {}'.format(qx, qy))

px = int(input('Insert the X coordinate: '))

py = int(input('Insert the Y coordinate: '))

qx = px

qy = py

if self.is_valid(px, py):

self.current_state[px] = 'X'

self.player_turn = 'O'

break

else:

print('The move is not valid! Try again.')

else:

(m, px, py) = self.max_alpha_beta(-2, 2)

self.current_state[px] = 'O'

self.player_turn = 'X'

Playing the game is the same as before, though if we take a look at the time it takes for the AI to find optimal solutions, there’s a big difference:

.| .| .|

.| .| .|

.| .| .|

Evaluation time: 0.1688969s

Recommended move: X = 0, Y = 0

Evaluation time: 0.0069957s

Recommended move: X = 0, Y = 1

Evaluation time: 0.0009975s

Recommended move: X = 2, Y = 0

Evaluation time: 0.0s

Recommended move: X = 1, Y = 2

Evaluation time: 0.0s

Recommended move: X = 2, Y = 2

It's a tie!

After testing and starting the program from scratch for a few times, results for the comparison are in a table below:

| Algorithm | Minimum time | Maximum time |

|---|---|---|

| Minimax | 4.57s | 5.34s |

| Alpha-beta pruning | 0.16s | 0.2s |

Conclusion

Alpha-beta pruning makes a major difference in evaluating large and complex game trees. Even though tic-tac-toe is a simple game itself, we can still notice how without alpha-beta heuristics the algorithm takes significantly more time to recommend the move in first turn.

Source: here